It was 1973 when Gene and I settled into a pattern of living together in my Canoga Park, California apartment where I’d lived when I was married and where my toddler son, Jim, and I continued to live after my divorce. Gene was the only black person in the complex. We socialized with our neighbors and lived happily in our little neck of the woods until there was a turnover in the managers.

I was sitting poolside, watching Jim play in the wading pool, when two police officers entered the front gate and walked towards the main building. Gene said he was shooting pool when the policemen approached him and said, “Put your pool stick down,” as they fingered their billy clubs. He looked for a place to hang up his stick and again heard, “Put the pool stick down!” Confused, he laid the cue on the table. The officers handcuffed him stating, “You’re under arrest.” They didn’t tell him why. This was his first arrest in 32 years and that included twenty years growing up in Alabama, the epitome of the Jim Crow South, where young black men were frequently arrested for nothing. He’d never expected treatment like this in California.

Soon, the officers I’d seen earlier, marched Gene, handcuffed and bewildered, out the door and down the stairs. They paraded him past the pool area. Jim started to cry. Confused and shaken, I grabbed Jim’s hand and ran back to our apartment.

I paced back and forth holding my son and patting his back to calm him. All the while I wondered what was happening, what I should do, and unable to do anything but wait.

Later Gene told me that the police drove ten miles to the Van Nuys jail and placed him in a cold room alone with a table and two chairs—just like on Law and Order. A detective entered. “Do you know why you’re here?” he asked.

“I haven’t a clue,” Gene answered.

“Do you know a Vivian Kowalski?”

She was the new manager, and Gene told them he knew her. The agent explained that she had accused him of putting a screwdriver to her side and demanding that she have sex with him or he would harm her two children. He was horrified and told the cops that was a lie. In fact, the police had merely asked her how things were going. Apparently, she’d taken that opportunity to invent a story, a racial hoax, an act of fabricating a crime and blaming it on a person of another race.

Gene had been marched away at one o’clock. I received his one promised phone call two hours later. “Annie, I’m at the Van Nuys jail,” he said. “I need you to bail me out.”

“I’ll get there as soon as I can,” I answered.

Once out on bail, Gene phoned the apartments’ parent company, Larwin, and explained what had happened. He told them, “This is a case of racial housing discrimination. Your managers didn’t like a black man living with a white woman, so they accused me of a felony as a ruse to get me out of the complex—even if that meant going to jail!” Larwin tested Gene’s theory and fired the managers.

On the day of Gene’s arraignment, we sat on a wooden bench in the cavernous marble hallway of the criminal justice building where we met Larry Trygstad, the attorney I had hired. We held hands. After an hour, Larry left and returned with the news that Vivian hadn’t shown up. The charges were dropped. The nightmare was over. We felt vindicated to learn that Vivian and her husband had fled to Canada, from whence they had come, to escape prosecution for violating the Fair Housing Act, Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968.

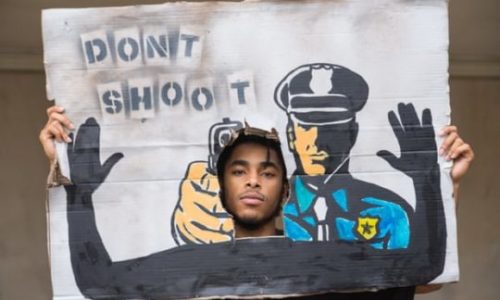

Gene and I rethought a sacred principle of the American criminal justice system, holding that a defendant is innocent until proven guilty. Now we knew that an accusation was all it took for a person to get arrested—especially for a black man.

Forty-six years later Robert Mitchell, a black California man, sued the city of Bakersfield claiming he was wrongfully arrested after refusing to give officers his name during a traffic stop. He asserted his rights because “I’ve had past incidents where I’ve been arrested and it was unlawful and I didn’t know my rights.” The city agreed to a $60,000 settlement in 2019, and unfair treatment of black men continues.

This post was submitted by Los Angeles writer Ann Carnes, at work on her memoir: Miss Ann and Her Man.