2020—The Year of Seeing Clearly, by Ann Anderson Evans

I love men, prefer their company, and sympathize with them, maybe because I had two brothers. Men don’t have it easy—for millennia, they’ve been suffering oceans of anxiety because they had to support their families and fight our wars, but I’m a woman, and I…

memoir is best told as podcasts—as a spoken story—with no end yet in sight. Maybe you need to make a couple of YouTube videos that capture best the story you are remembering. Maybe it is a book but it’s a combination of journal entries and running commentary, or a collection of free-standing chapters each one about a single family member and how he or she shaped your journey. Or maybe it consists entirely of letters, emails, and texts written between you and a loved one that capture the essence of love and trust, betrayal and forgiveness. I don’t know, and neither does that person out there whispering in your ear that your memoir needs to have the shape of a novel.

memoir is best told as podcasts—as a spoken story—with no end yet in sight. Maybe you need to make a couple of YouTube videos that capture best the story you are remembering. Maybe it is a book but it’s a combination of journal entries and running commentary, or a collection of free-standing chapters each one about a single family member and how he or she shaped your journey. Or maybe it consists entirely of letters, emails, and texts written between you and a loved one that capture the essence of love and trust, betrayal and forgiveness. I don’t know, and neither does that person out there whispering in your ear that your memoir needs to have the shape of a novel.

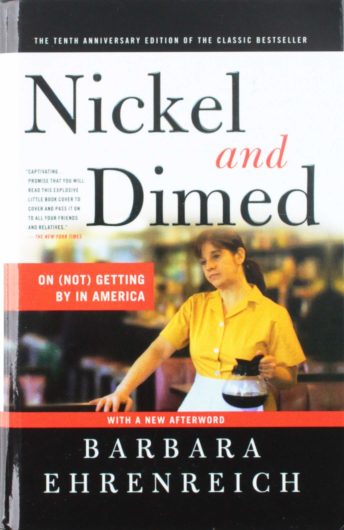

Perhaps you are writing about income inequality based on a series of jobs you have held that barely allow you to make ends meet; don’t just rail against those you believe are guilty of making your life the way it is, but back your experience with information about how economic conditions get to be the way they are. (For an example, see the now classic Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich.)

Perhaps you are writing about income inequality based on a series of jobs you have held that barely allow you to make ends meet; don’t just rail against those you believe are guilty of making your life the way it is, but back your experience with information about how economic conditions get to be the way they are. (For an example, see the now classic Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America by Barbara Ehrenreich.)

Concerns about hurting family and friends are some of the most worrisome for memoirists. My advice? Quit obsessing about it and get on with the writing. Plenty of would-be memoirists have stopped themselves before even getting started, due to such concerns, and many who have made it past the starting line, never finish their memoir because they freak out part of the way through and quit.

Concerns about hurting family and friends are some of the most worrisome for memoirists. My advice? Quit obsessing about it and get on with the writing. Plenty of would-be memoirists have stopped themselves before even getting started, due to such concerns, and many who have made it past the starting line, never finish their memoir because they freak out part of the way through and quit.

finding compassionate ways to tell their truths—which is the real work of memoir.

finding compassionate ways to tell their truths—which is the real work of memoir.