| I’ve been thinking more this month about how to find your way into the wealth of material that is your life, and compose from it a memoir.

I wrote about this last month, and actually in all my columns since the pandemic began, and the reason this remains on my mind is because so many people really are sitting down and doing the work they have so long desired: crafting into words the stories of their lives.

And yet, the thing that‘s coming up almost across the board with what I’m seeing from these manuscripts is a fundamental misunderstanding of the difference between memoir, and family history, or autobiography.

Family history and autobiography are valid, good, and important forms of story telling, but they are not memoir, and when one sits down to write a memoir, and especially if one sits down to write a m emoir harboring dreams of finding an agent and a New York publisher, it’s vital this difference be understood from the start. emoir harboring dreams of finding an agent and a New York publisher, it’s vital this difference be understood from the start.

One of the key signifiers of a well-conceived memoir is a good premise.

Often I talk about identifying heart of the story as key to successfully structuring a memoir. It is, but this month I’m taking heart of the story one step further, to premise.

What’s the difference?

At a rudimentary level, heart of the story is a topic, a concept, around which your shimmering images pivot, and it is stated as a noun. For example: perseverance, or loss, or discovery. And while heart of the story gets you to the core idea that animates your memories, premise is more directive. Your premise actually shows you the path your memoir must follow. It reveals structure.

Rather than being just one word, the premise is a catchy sentence, often a cliché, like: Slow and steady wins the race, or when one door closes another opens.

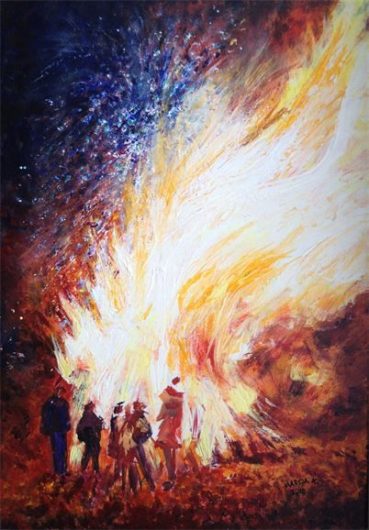

Why is a premise clich é like? Because story premises are repeated over and over again in the world of literature, and entertainment, and have been forever—since the campfire—and will continue to be. é like? Because story premises are repeated over and over again in the world of literature, and entertainment, and have been forever—since the campfire—and will continue to be.

Premise is at the root of what the story does over the course of the pages it fills—what it shows with all the information, scenes, characters, memories, conversations, and reflections you weave onto the page.

If you begin your “memoir” with intricate descriptions of your family tree—people and places and connections and the eccentricities of Great Uncle Randolph—and yet you’ve determined, for example, that the premise of your personal story is slow and steady wins the race, a reader may have a hard time figuring out why she is encountering reams of uncurated information about three generations of your extended family in the opening chapters. And you may have a hard time, too, figuring it out, once you’re really thought about it.

Having an apt premise makes clear just what stuff doesn’t belong in your memoir.

So, in the coming weeks, if you’ve been writing lots of shimmering images, and you now know the heart of your story, take it a step farther this month and push that one word, that concept—let’s say perseverance—toward a story premise. Maybe all those memories of you being persistent and dogged and stubbornly individualistic—through great odds and hardship—reduce to the tidy premise of: Slow and steady wins the race.

If so, go about the business of patching together your shimmering images with that underlying premise guiding the order in which you present them, and get rid of everything that doesn’t contribute to that unfolding story.

Or maybe the heart of your story is loss, and the premise is: When one door closes another opens. Whatever the heart of the story, there is a premise that follows from it. Look at the material of your life and see what themes persist.

A premise may not always be a cliché, but it is always a small, simple statement that rings true for human nature. Once you have that statement, your work of constructing a memoir will be easier. Your premise will keep you from wandering into tantalizing, but not relevant material. |