April 5, 2010

My mother was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, metastasized to the bone, on January 14, 2010. Forty-five days later she was dead. I spent those last days with her, as companion, caregiver, friend, daughter, cook, nurse, and gate keeper to all who wanted access but to whom she denied it. I was the border police.

It was a horrible and brilliant shining journey, and I was spent at its end.

To understand the next piece of this story, you may need to be an animal lover, and if you are, you will “get” why I am taking off for new horizons . . .

Nine days after my mother slipped to the other side of the Veil, my beloved kitty cat, E. Flynn, my best friend in all the world, and really, all I had left, was killed by a car. Flynn was a like a dog in kitty clothing. He ran and jumped and played, went for walks with me, climbed to the highest limb of any tree just to show me he could do it, then flew to the ground. He had one bad eye, injured when he was abandoned in the beginning of his life, a little less than a year ago, and I called him Pirate Flynn. He did not know fear.

When he died, so close to my mother’s departure, the world went quiet, like huge cotton balls had been stuffed into every cranny around me. All I could think was: I must go away.

And so off I go to Europe with one pack on my back and a railpass in my pocket. This is not such an odd thing to do any more, but then I am not 20 years old, or even thirty . . . or forty . . . .

But why Europe? Why not China, or Haiti, or Mexico?

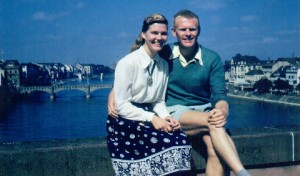

Before I learned my mother was terminally ill, I was working on a book of literary nonfiction. At the core of its concept lies a journey my parents—both dead now—took when they were twenty-three and twenty-five. Off they went to the Continent by steam ship with bicycles. Soon they discovered the bikes were too much trouble and they sold them, taking up what all the young Brits and Australians were doing at the time: auto-stopping, a precursor to the wave of young people hitchhiking Europe in the 1960s and 1970s.

But this was 1951, six years after the end of the Second World War. The Continent was still devastated, and there were no Americans on the road. None except my parents, it seemed.

But this was 1951, six years after the end of the Second World War. The Continent was still devastated, and there were no Americans on the road. None except my parents, it seemed.

That trip shaped my life. What my mother, Nancy, and my father, Bill, saw, and felt, and learned fueled the parents they became two years later, first with my brother and then another three years later with me.

Our home was filled with art, decorative items, fabric, and dishes influenced by that epic journey—another oddity, because the location of our home was small town Nebraska.

But more, my childhood was woven with my parents’ tales, the adventures of two young rogues. And it was the weight of those stories, what they named as valuable, that has been at the center of decades of my decisions. Really, how I chose to live my life—all those years I had parents.

I am looking now for the next story, for a way to put all that has gone before into some new context, and to name that which will guide all that is to come.

As I set out to trace the spine of my parents’ journey, I am looking too, for the missing pieces of a book that waits completion.

I’ll be posting here as I go.