Writing Memoir To Fit This New Time

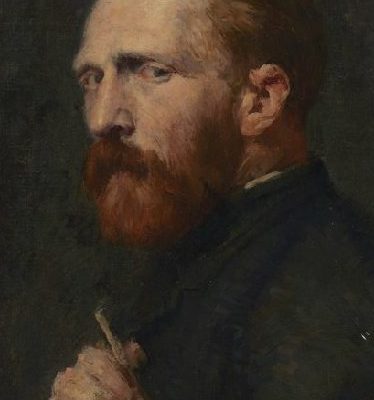

For thirty-five years, I have helped writers of all skill levels achieve their goals of putting together stories about their lives, ranging from magazine-like travelogues, to family portraits bordering on biography, to thinly veiled fictional accounts, to book length memoirs of childhood and mid-life adventures.…

only end up being normal for a week or two. In the midst of it, I’ve done my best to keep writing—as a lifeline—and what I’ve remembered is that during times of transition and duress, returning to the basics is the most grounding of activities.

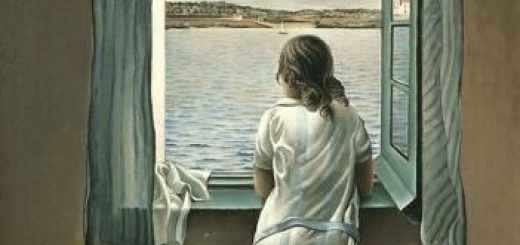

only end up being normal for a week or two. In the midst of it, I’ve done my best to keep writing—as a lifeline—and what I’ve remembered is that during times of transition and duress, returning to the basics is the most grounding of activities. social expectations, I urge you toward the simplest of creative endeavors: Make a bulleted list of the shimmering images pinging around inside your mind—just a word or two to capture each (so you can call it back later).

social expectations, I urge you toward the simplest of creative endeavors: Make a bulleted list of the shimmering images pinging around inside your mind—just a word or two to capture each (so you can call it back later).

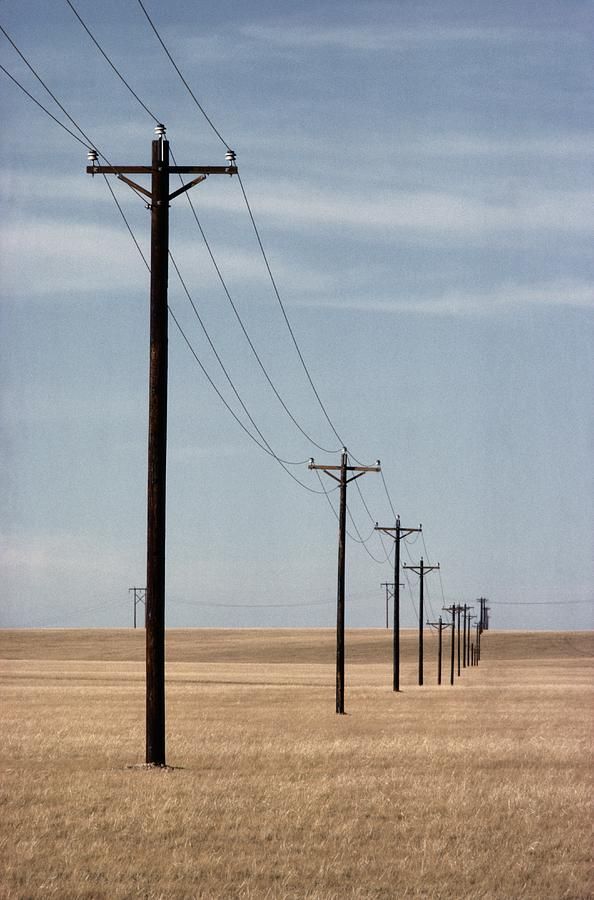

As you work with this winnowed chunk of life, more memories will jump up—some joyous, some the color of dirt. They are all important, especially the ones that come roaring back. They are the poles upon which you hang the story line. They will lead you to the heart of your story.

As you work with this winnowed chunk of life, more memories will jump up—some joyous, some the color of dirt. They are all important, especially the ones that come roaring back. They are the poles upon which you hang the story line. They will lead you to the heart of your story. trust in yourself, because you can’t get to an outline for your memoir until you figure out what your memories are illuminating. Writing a memoir is not just about the events; it’s about what they mean.

trust in yourself, because you can’t get to an outline for your memoir until you figure out what your memories are illuminating. Writing a memoir is not just about the events; it’s about what they mean. ou’ve named.

ou’ve named.

memoir is a re-creation of a truth, your remembered experience of an event, or a time, or a period in your life—what it meant to you, how it affected you, how it shaped your psyche and heart, how it shaped your future days. And since that is what I believe, my take on the dialogue dilemma in memoir is that you create what best represents the character, the moment, and the remembered essence of the truth that you took away from the scene.

memoir is a re-creation of a truth, your remembered experience of an event, or a time, or a period in your life—what it meant to you, how it affected you, how it shaped your psyche and heart, how it shaped your future days. And since that is what I believe, my take on the dialogue dilemma in memoir is that you create what best represents the character, the moment, and the remembered essence of the truth that you took away from the scene. mistakes we all make, the pressures of society, the culture of the times? All these variables affect why people behave the way they do. The memoirist who can keep that in mind, writes, I believe, a more realistic story, a more human story.

mistakes we all make, the pressures of society, the culture of the times? All these variables affect why people behave the way they do. The memoirist who can keep that in mind, writes, I believe, a more realistic story, a more human story.