12 Guilty Pleasures for Memoirists

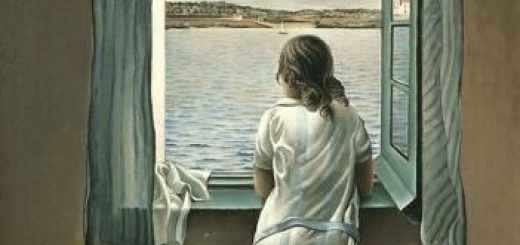

Writing memoir is hard work. You spend hours gazing into your past, mining memories for emotions and details, and coming to insights that

Author, Editor of Memoir & Narrative Nonfiction

Writing memoir is hard work. You spend hours gazing into your past, mining memories for emotions and details, and coming to insights that

You haven’t heard from me in awhile. I’ve been in hibernation. Ever have one of those periods? I’ve been finishing a book and–let’s face it–grieving the loss of my mother and my dad, too, who died a few years earlier. I’ve been trying to figure…

I’ve been absent from this newsletter for some time. Life intervenes, as the saying goes, but because I am passionate about crafting stories from life, I thought I’d tell you a story about why I’ve been gone for awhile, and in that story you might find a reason to keep working on your memoir in this new year.

My brother died. Simple words. But he was my only brother.  My only sibling. My big brother, a god in my mind—an image formed early as a little girl: he was so much taller, and he could make full sentences. He ran around the neighborhood, returning with rocks and feathers in his pockets and smelling of earth and trees. He was so much fun because he was always up to no good and he always charmed the neighborhood ladies to get out of trouble. How could I not fall in love young?

My only sibling. My big brother, a god in my mind—an image formed early as a little girl: he was so much taller, and he could make full sentences. He ran around the neighborhood, returning with rocks and feathers in his pockets and smelling of earth and trees. He was so much fun because he was always up to no good and he always charmed the neighborhood ladies to get out of trouble. How could I not fall in love young?

But more: He was the only living member of my family. The last one who knew the stories, the settings, the people, the only one who knew exactly what was meant if I said: Sheldon, or the Point, or the Old Barn, or the coons.

I imagine some of you have had this kind of ending in your life. It’s a trap door feeling, the bottom swinging out, and I wasn’t prepared for it. And so, this past year has been a steep climb up a steep hill,  or what they call a “coming to terms.” As such things go, I’ve been tangled in the process of crafting a new story for my life, about what happens to all those stories once shared, and what the world means devoid of family.

or what they call a “coming to terms.” As such things go, I’ve been tangled in the process of crafting a new story for my life, about what happens to all those stories once shared, and what the world means devoid of family.

Yet even now, at the end of this long year of silence, I have no tidy nugget of insight to share with you about all that. What I do know, and what I want to tell you has to do with your memoir: you must write it, and I emphasize you.

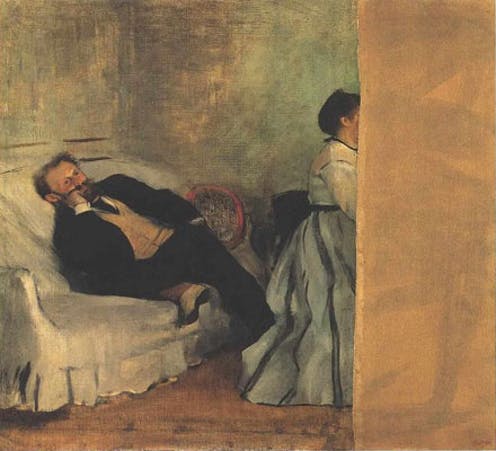

When my brother died, what I witnessed from the people around him further shocked me. The stories they told about him were not the stories of my brother! Not the brother I knew! They were not the stories I held in my heart about who he was in the world and what his life meant! I had a suspicion, too, that they were not the stories my brother would have told to corral the meaning of his adventures and challenges.

What I know is simple and pressing: If you want to assign the meaning of your experience, you must be the one to write it.

Because, I assure you, if you do not, other people will. They will craft the meaning of your actions and words. They will weave the narrative that goes out into the world and remains. They will be the author of your life, and chances are, it will not be the truth you know in your heart.

I don’t know about you, but for me, this last year has been one long blur of unexpected events, time consuming changes to the daily round, and disorienting new “norms” that only end up being normal for a week or two. In the midst of…

These past months of lockdown have given me many manuscripts to evaluate, and ample time to think about why so many memoirs need revision, even when the writer thinks the story is done. Here’s how the root problem can arise: If you write memoir from…

|

When the pandemic started, I wrote about using stay-at-home time to work on your memoir, and then followed up with a column on the basics of organizing your shimmering images—your vivid memories.With back-to-school mentally kicking in (even if back-to-school is unfamiliar), it’s time to find…

Last month I wrote about using your time, while at home, to work on a memoir and suggested the basics for getting started. This month here’s the next step: what to do with all those memories you’ve been stockpiling, or with all the stories you’ve…

We are all going to have time eddying around us in these coming weeks, as life shifts into a new and unfamiliar rhythm, but once we strike that rhythm—whatever it is for each individual household—once we get past the panic and stock piling of supplies, move beyond the fast-driving-fast-shopping wave of insecurity, we are going to sink back into the couch/kitchen chair/bed/bathtub and say: What now?

And that “What now?” question speaks to many levels of our lives, but one of those levels is: How do I respond as an artist?

I say: Write.

If we are resourceful, a good outcome from all this staying home, will be a huge spurt of originality and creativity—if we make it so. We must find positive ways to channel the surge of energy currently electrifying our hearts and homes and expressing itself as skittering social media interaction.

Instead, do everything you can to refocus that energy and to use it to produce something original.

Personally, I’m banking on this being a time when we all get to work on the books we’ve been dreaming—a memoir, autobiography, a novel based on real events, a mystery perhaps, a completely invented world of science fiction. Whatever your  dream, now is the time make it a reality.

dream, now is the time make it a reality.

If you are writing a memoir, here is your first assignment.

Stay-At-Home Memoir Writing Assignment #1:

1) Take our a sheet of paper, or open up a new word processing document and bullet item list some memories that pop into your mind. No order. No reason. No justification. No clue why they may be coming to you right now—and no need to figure it out. All you’re doing is remembering.

2) List your memories with some phrase that will help you conjure them again the next time you come back to this list—Edie’s birthday party; that sunset off the balcony when Trevor came home; oatmeal in Grandma’s kitchen; the stairwell at night. Whatever.

3) Tomorrow do the same. Just list some memories—snippets of remembrance: a face laughing at a joke you once told; a shared slice of pie with a best friend one sunny afternoon when you both told secrets and giggled; that first home run you hit and the jolt of adrenaline as you raced for first base.

Ultimately, when you’ve amassed a good long list of these Shimmering Images, as I call them—shiny little memory shards—you will begin writing them. One-by-one. No order. No attempt to connect them, unless it should happen naturally. For now, just list them.

That, my friends, will get you on the path of writing your memoir, and give you a way to channel your energy and be creative.

Remember: In the end it will be the artists who tell the story of this time. Sound overblown? Just look at history. What do we remember and value above all else? What fills our museums? The creative output of generation upon generation upon generation.

Make art. Write your memoir.

People talk. And in your memoir, even if you are the kind of writer who leans more toward the meditative/reflective style of memoir writing—at some point, your characters will open their mouths and speak. So, the question becomes: Are you allowed to invent? Obviously, you…

It was 1973 when Gene and I settled into a pattern of living together in my Canoga Park, California apartment where I’d lived when I was married and where my toddler son, Jim, and I continued to live after my divorce. Gene was the only…

I love men, prefer their company, and sympathize with them, maybe because I had two brothers. Men don’t have it easy—for millennia, they’ve been suffering oceans of anxiety because they had to support their families and fight our wars, but I’m a woman, and I feel as if I’ve been crawling out from under a rock over the last few decades. Our stories are finally beginning to be told well, and it’s a relief to see some sunlight.

An unexpected revelation tripped me up recently, causing me to to burst into an emotional rant, something I almost never do. A male friend confessed that he liked dressing up in women’s clothes. It was a secret that he’d shared with only a few people and he made me promise to hold his secret close.

In due time, he showed me the clothes stored in a dresser standing in an obscure corner of his attic. They reminded me of the mother in Psycho. Frills, lace, little flowers on the polyester, those small scarves we used to wear on our heads like the Queen. Even if a woman stepped out in those clothes, she would be considered an odd throwback. But hey that’s what he liked. When I asked him what had drawn him to cross dressing, he said, “I have always been curious how it would feel to be a woman.”

That’s when the rant happened.

“You think wearing frilly underwear is what it means to be a woman? It’s more like keeping blood off that underwear when you have your period, those several days every damn month, every month, where you have to go to work with cramps. It’s having men turn glassy-eyed and dismissive when you give your opinion about the New York Knicks. But you know the worst thing? It’s not the pain of menstruation and childbirth or the denial of certain professions or jobs, it’s the torture of thanking the guy for doing the shopping, and him saying ‘you’re welcome,’ and then you go into the kitchen and find he’s left the bags of groceries on the kitchen counter for you to put away.

“Or him feeling proud of himself for emptying the dishwasher and then going out to play baseball with the kids, leaving you to sweep the porch, clean out the refrigerator, sew a button on a coat, wipe up the dog’s muddy footprints in the front hall, the dozen things that he hasn’t even noticed.

“And you’re not supposed to get angry because that would upset the relationship, so you remind him, gently, of chores, and he does them, because you told him to. He’ll comply when you give him a “honeydo” list—men giggle about honeydo lists. But why can’t they figure out what needs to be done? You’ve been at work all day and have to get up tomorrow morning, too.

“After getting angry, and cajoling, and making lists, and begging him to be more engaged, you have to give up because in the end all you feel is anger, and if that anger comes out, you’ll get divorced.

“That’s what it’s like to be a woman.

“And let me remind you that when I was a girl we had to wear girdles and stockings and we couldn’t wear pants except on weekends in the woods.”

I stopped to catch my breath, though a hundred further insults to my dignity were flooding into my brain.

My friend was fascinated. “Wow.”

“You might say that times have changed, that men are woke now, but I don’t think it’s changed so much. Women still do most of the child care even if they have a job, and they still resent it. So some women just stop doing housework altogether and that leaves the world living in shit, but that’s the only way they see to stop being pounded by resentment.”

I was finished for the moment, and I sat back and looked at my friend. He smiled and said, “I still like wearing women’s clothes,” and we laughed together.

Sometimes the world is so ungainly that laughter is the only refuge.

This post was submitted by Ann Anderson Evans, author of the award-winning Daring to Date Again: A Memoir (She Writes Press, 2014).

Click here to read my latest blog post about Owning Your Story.

What I learned when the last of my family died . . .